- Causes of Future Sea Level Rise

- Elevation Maps

- Will we really lose all that land?

- Sea Level Rise Planning Maps

3.1.1 Rolling Easement Zoning and Other Local Regulations

Except in parts of Texas,[138] a local government has zoning authority in every coastal community in the United States.[139] Zoning typically involves a map that divides all land into several categories, called “zones.” Land in a given zone need not be contiguous, but zoning requirements are uniform within the zone.[140] Common names for zones include agricultural, residential, rural residential, commercial, commercial miscellaneous, industrial, conservation, and open space. [141] Localities often publish large tables that list all the activities that are prohibited, allowed, or allowed only with a variance or special permit.[142] Zoning may control densities of development, sizes of lots,[143] shapes of land parcels,[144] and particular activities on the land.[145] If an activity is prohibited in all zones, it may be shown as prohibited in the zoning table, or simply prohibited by ordinance.

Some localities have overlay zones, which are—in effect—a second set of maps and requirements.[146] For example, a floodplain map with associated requirements for buildings in the floodplain is a type of overlay zone. The actual requirements are the same as if every zone were subdivided into two zones, floodplain and non-floodplain; but it is often administratively easier to enact a second set of requirements than to modify each of the zones. Courts have occasionally rejected overlay zoning, in effect requiring localities to explicitly subdivide each zone to achieve the same result.[147] For generality, we assume that a rolling easement is added to the regular zoning, rather than as an overlay district.

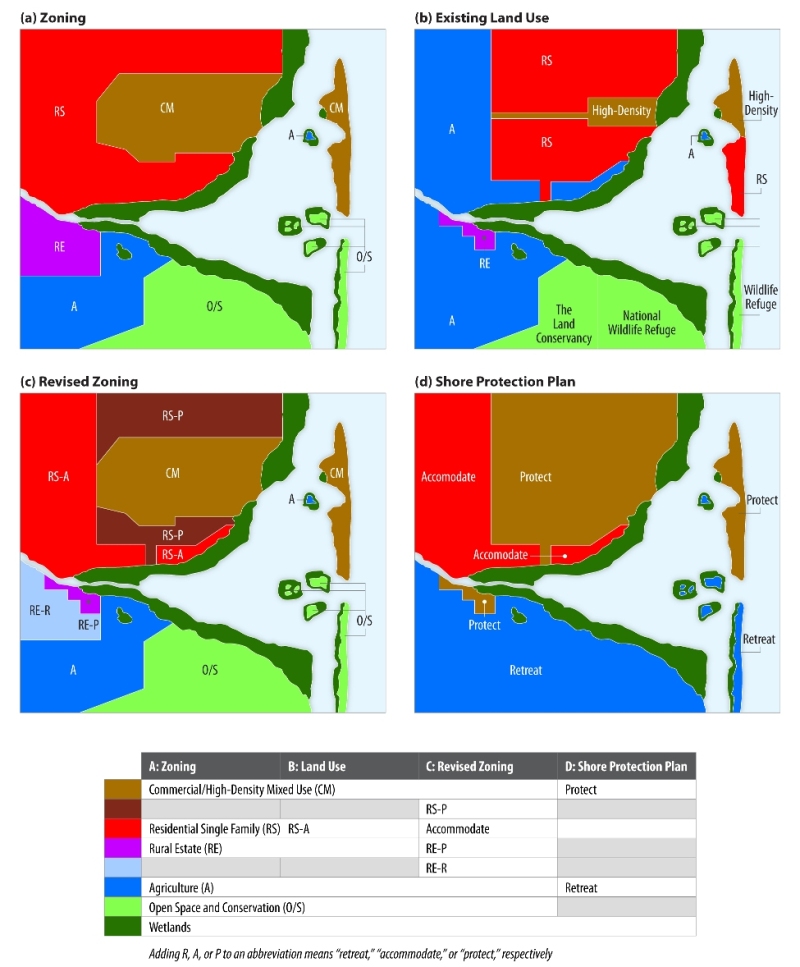

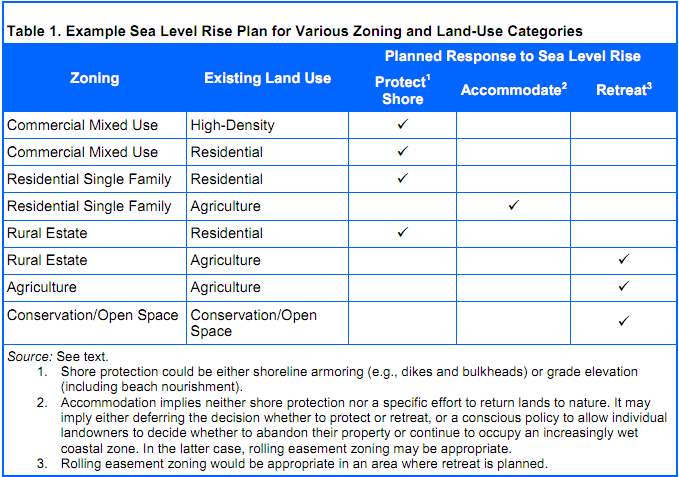

Consider a locality that has five zones today: open-space/conservation (O/S), agricultural (A), rural estate (RE), residential single family (RS), and commercial mixed use (CM) (see Figure 8a). Suppose the locality creates a land use map defining the existing land use, as shown in Figure 8b: The O/S lands are all owned by either a federal wildlife refuge or The Land Conservancy (TLC). (In this primer, TLC is a hypothetical local land trust that that buys and accepts donations of land and conservation easements for environmental purposes.) The CM lands are entirely developed, with a combination of commercial, high-density residential and single-family homes that could be converted to a higher density in the future under the existing rules. The RS and RE are each partly developed with residential homes, and partly agriculture, which is a permitted land use in residential areas. Let us suppose that the locality decides that the existing development should be protected, while the A, O/S, and undeveloped RE lands should not be protected but instead should be available for wetland migration. Let us also suppose that no decision is reached regarding undeveloped RS lands: On the one hand, it may be feasible to require an agreement to allow wetland migration as a condition for future construction; but on the other hand, protecting the moderate-density development is more likely to be cost-effective than protecting the low-density RE. (Table 1 summarizes these planning assumptions.) Figure 8d maps the three categories of shore protection.

Figure 8c shows a simple rolling easement zoning scheme, which:

- Splits the RE zone into two zones: rural estate protect (REP) and rural estate retreat (RER) based on Figure 8d;

- Splits the RS zone into two zones: residential single-family protection (RSP) and residential single-family accommodation (RSA);

- Amends the zoning ordinance to add “shore protection structures” and “increases in land elevation grades” to the list of prohibited activities for zones A, OS, and RER.

If the locality is also interested in preserving access along shores where protection is allowed, it can amend the zoning to prohibit shore protection except where a public pathway is immediately inland of the shore. The logical result will be that any landowner who wants a building permit for shore protection will dedicate a public pathway.

For this report, TLC is a hypothetical local land trust that buys and accepts donations of land and conservation easements for environmental purposes.

The actual zoning scheme may have to be more complicated to avoid unintended consequences. A community intending to prevent shore protection will not usually intend to prohibit waterfowl impoundment dikes in OS lands. Some re-grading may be necessary for roadbeds. A levee designed to prevent flooding along a stream 100 feet above sea level may look like a dike, but it will not prevent inland migration of wetlands. Re-grading along hills may be needed for home construction or farm drainage.

Two common procedures can help avoid unintended consequences. First, activities that sometimes have an approved purpose can be permitted only with a special exception.[148] Second, all the zones can be divided into a coastal zone and an inland zone, with the rolling easement restrictions only applying within the coastal zone. Some localities already have coastal zones within their land use zoning ordinances.[149] Elsewhere, state laws have created coastal overlay zones, with state requirements, which we discuss in the next section.

Zoning is not the only form of local land use regulation. Communities that particulate in the National Flood Insurance Program have floodplain regulations.[150] Some of these regulations sharply discourage development in floodplains.[151] Many localities also have wetland regulations designed to avoid harm to beaches and mudflats, as well as vegetated wetlands. In Massachusetts, the wetland protection rules for several towns prohibit both shore protection structures and grade elevation within 50 feet of the shore, with the explicit purpose of ensuring that wetlands and beaches migrate inland as sea level rises.[152] Calvert County, Maryland has cliff retreat regulations that prohibit cliff armoring, to preserve the habitat of Tiger Beetles.[153]

In Massachusetts, the wetland protection rules for several towns prohibit both shore protection structures and grade elevation within 50 feet of the shore, with the explicit purpose of ensuring that wetlands and beaches migrate inland as sea level rises.

[138] In Texas, municipalities have zoning authority, Tex. Loc. Gov't Code Ann. § 211,

but counties only have such authority in a few places, such as parts of Padre

Island in Cameron and Willacy counties. See also Jennifer Evans, Guide to Texas Zoning

(College Station, Texas A&M Real Estate Center 1999). Most undeveloped and lightly developed

lands are not within a municipality.

[139]

Roger A. Cunningham, Land-Use Control—The

State and Local Programs, 50 Iowa L.

Rev. 367, 368 (1965) .

[140]

Standard State Zoning Enabling Act

§ 2.

[141]

See, e.g., Prince George's County [Maryland] Zoning

Code § 27-441.

[142]

See, e.g., id.

[143]

Standard State Zoning Enabling Act

§ 1.

[144]

See, e.g., Prince George's County [Maryland] Zoning

Code § 27-441 at 14 (specifying zones

where flag lots are allowed or not) and Prince George's County [Maryland] Subdivision

Regulations § 24-138.0 (flag lot

specifications). A flag lot is a parcel with no true front yard along the

street, with a narrow strip for a driveway to connect the parcel to the street.

A sketch of such a lot often resembles a flag (the main parcel) on a pole (the

driveway).

[145]

Standard State Zoning Enabling Act

§§ 1–2.

[146] Julian Conrad

Juergensmeyer & Thomas E. Roberts, Land Use Planning and Control Law,

§ 4.21,

Hornbook Series, West Publishing (1998). See also John R. Nolan, Well Grounded: Using Local Land Use Authority to Achieve Smart

Growth, 209–213 (Environmental Law Institute,

2001).

[147] E.g., Marble Technologies, Inc. v. City of Hampton,

690 S.E. 2d

84, 88–90 (Va. 2010) (rejecting an overlay zone based on map boundaries

delineated under the Coastal Barrier Resources Act, based on the Dillon

Rule) and

Farmers for Fairness v. Kent County, 2007 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 56 (Del. Ch., May 1, 2007)

(holding

that the Coastal Zone Protection Overlay Ordinance violated the

uniformity requirement of the zoning

statute).

[148] A special exception is a use permitted within a zoning

district, but subject to certain, specific conditions. A public hearing is necessary for

collecting the necessary information on whether the exception will be

granted. See, e.g., Standard State Zoning Enabling Act §7

(authorizing a Board of Adjustment to grant special exceptions) and

Prince George's

County [Maryland] Zoning Code § 27-441 (allowing some uses only with a special exception). A

common standard for “determining whether a requested special exception … should be denied is whether there are

facts and circumstances that show that the particular use proposed at the

particular location proposed would have any adverse effects above and beyond

those inherently associated with such a special exception use irrespective of

its location within the zone.” Schultz v. Pritts, 291 Md. 1, 22

(1981).

[149] See

e.g. Critical Areas Commission for the Chesapeake

and Atlantic Coastal Bays, Frequently Asked Questions, http://www.dnr.state.md.us/critical area/faq.html#18, (undated)

(explaining that

localities in

Maryland have generally incorporated Chesapeake Bay Critical Area Act

limitations into their zoning); Town of Eastham, Massachusetts, Zoning By-Laws: Flood Plain Zoning; and Marble Technologies, Inc.. v. City of Hampton, 690 SE 2d 84, 88–90

(Va. 2010).

[150] See e.g. Federal Emergency Management Agency, The

National Flood Insurance Program, http://www.fema.gov/plan/prevent/floodplain/index.shtm (cited on February 1, 2011) (“Currently over 20,100 communities

voluntarily adopt and enforce local floodplain management ordinances that

provide flood loss reduction building standards for new and existing

development.)

[151] See, e.g., CCSP, supra note 3 , at 209–210 (discussing

two counties in Delaware that prohibit subdivisions and discourage new

construction in the 100-year coastal floodplain).

[152] Town of Chatham

Wetlands Protection Regulations,

§§

202(3)(c),

203(3)(c), 206(3)(b) (prohibiting grading and construction within 50 feet of

beaches, dunes, or salt marshes).

But cf. id. §

205 (3)(a)(1)

(allowing hard shore protection structures along banks above wetlands and beaches for

homes built or approved before 1978).

[153] See, e.g., infra

notes 165

and 286,

and accompanying

text.

This page contains a section from: James G. Titus, Rolling Easements, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA‑430‑R‑11‑001 (2011). The report was originally published by EPA's Climate Ready Estuary Program in June 2011. The full report (PDF, 176 pp., 7 MB) is also available from the EPA web site.

For additional reports focused on the implications of rising sea level, go to Sea Level Rise Reports.

3.0 Legal Approaches

3.0 Legal Approaches