- Causes of Future Sea Level Rise

- Elevation Maps

- Will we really lose all that land?

- Sea Level Rise Planning Maps

6.1 The Rolling Design Boundary: Which Resources and Rights Roll Inland?

A rolling easement can be based on whichever definition of shoreline is most appropriate for achieving the objectives of the policy. Rolling easements can use more than one rolling design boundary if, for example, it is important to prevent seawalls or new buildings on the beach, but the easement holder or government regulator can tolerate existing homes on the beach until they regularly stand under the runup of ocean waves (see Figure 2). More generally, a rolling easement can be designed to ensure that wetlands and beaches have room to migrate inland and that either:

- Existing public access (or a particular coastal ecosystem) along the shore migrates inland (Section 6.1.1);

- The area of public access (or habitat) initially shrinks before migrating inland. The public's access along the shore currently includes some areas inland of the rolling boundary; so as the shore erodes, the area of public access will decline until the rolling boundary reaches the existing inland limit of public access, after which public access will migrate inland. Alternatively, conservation areas currently preserve areas inland of the rolling boundary; so the area of shoreline habitat will decline until the rolling boundary is inland of what is now a buffer, at which point habitat zones will migrate inland (Section 6.1.2); or

- The rolling boundary is set landward of the current public access boundary, so the public will have more access along the shore than it has today (Section 6.1.3).

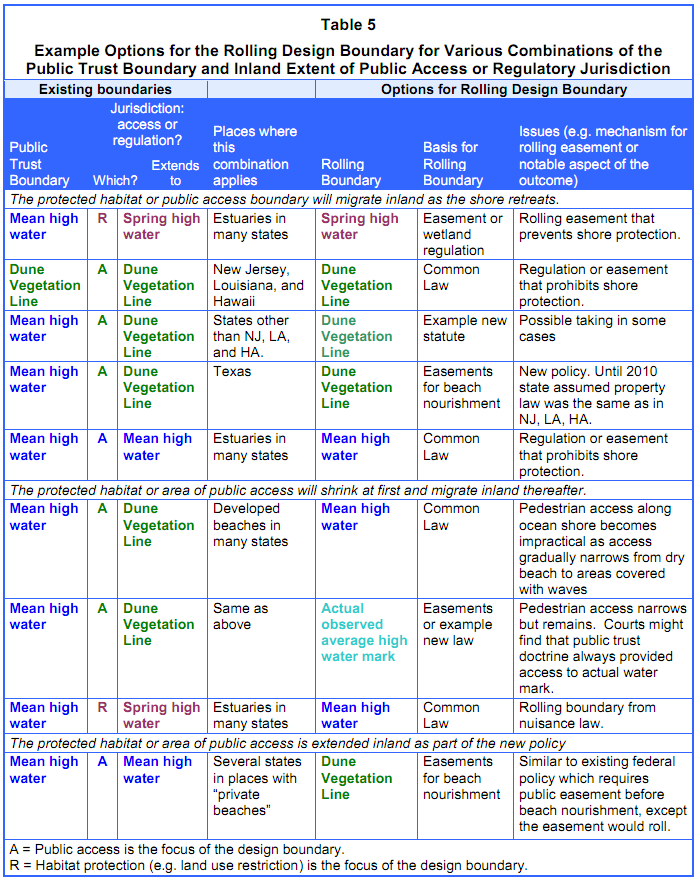

How each of these goals is achieved will depend on the existing inland boundary of public access or regulatory authority, and whether that boundary or a more seaward boundary migrates under the public trust doctrine (see Table 5). We discuss each of these three possible objectives in turn. We also briefly consider property rights issues and look at a few rolling easement approaches based on elevation or the passage of time, rather than a rolling design boundary.

|

6.1.1 All Existing Resources and Boundaries Roll Inland.

Preserving Beaches and Wetlands. The most commonly examined[474] approach to rolling easements is to use one or more boundaries that are already established. The rolling easement just ensures that the boundaries roll inland, typically by preventing shore protection. [475] Most existing regulatory rolling easement policies along ocean beaches prevent shore protection structures on or seaward of the dunes, but show flexibility on removal of buildings that are on the beach as a result of erosion,[476] unless they encroach seaward of the boundary between public and private land (often the mean high tide line). Many of the same states have rolling setback policies that limit new construction within a given distance inland of the dune vegetation line.[477]

|

|

Photos 30 to 32. Shore protection structures

can block the inland migration of mudflats,

vegetated wetlands, and estuarine beaches.

Top: a retaining wall along tidal flats in Westchester

County, New York (March 2003). Middle: a bulkhead

along a tidal marsh in Monmouth, New Jersey

(September 2003). Bottom: a bulkhead along South

Jamesport Beach in Riverhead, New York

(September 2006). Photo source: ©James G. Titus,

used by permission.

Photos 30 to 32. Shore protection structures

can block the inland migration of mudflats,

vegetated wetlands, and estuarine beaches.

Top: a retaining wall along tidal flats in Westchester

County, New York (March 2003). Middle: a bulkhead

along a tidal marsh in Monmouth, New Jersey

(September 2003). Bottom: a bulkhead along South

Jamesport Beach in Riverhead, New York

(September 2006). Photo source: ©James G. Titus,

used by permission. |

Rolling easement policies along marshes are rare. The design boundary is generally the upper edge of tidal wetlands,[478] or a given distance inland of the marsh.[479] Shore protection structures can block the inland migration of mudflats, vegetated wetlands, and estuarine beaches (see Photos 30 to 32). If preserving intertidal habitat is the goal, a policy can prohibit structures seaward of the inland edge of the particular habitat (e.g. below spring high water). If the goal is to preserve both tidal wetlands and a 50-foot buffer along the wetlands, structures can be prohibited within 50 feet of the landward boundary of the tidal wetlands. If the goal is to avoid flood damages or preserve floodplains, a rolling easement policy can prohibit new or rebuilt structures in the 10-year (or any other frequency) floodplain. In these three examples, a rolling easement could either require removal of all structures seaward of (or touching) the rolling design boundary, or allow nonconforming structures that were landward of the boundary when built to remain for a defined period or until repairs are necessary. Shore protection structures, however, will have to be removed regardless because they defeat the fundamental purpose of the rolling easement.

Public Access. A rolling easement does not always have to explicitly address public access to ensure that it migrates inland. Along estuaries, public access is generally up to the mean high water line according to the public trust doctrine[480]; as long as human activities allow the intertidal zone to migrate inland, the public will continue to have pedestrian access, albeit inland. Public access extends to mean high water along many ocean beaches as well.[481] (See Figure 3 and Section 2.2.2.) But along oceans, mean high water is out where small waves break during high tide, making pedestrian access impractical. This limited public access will automatically migrate inland, such as it is. In a few states, the public trust doctrine provides access up to the dune vegetation line. [482] As long as the dunes can migrate inland, the public access will follow in those states.[483]

Even in states where the public trust doctrine only provides access below mean high water, the public has access along some beaches up to the dune vegetation line, for reasons other than the public trust doctrine. In such places, a rolling easement must expressly articulate that access up to the vegetation line will migrate inland as the vegetation line migrates; otherwise, the line of public access will not migrate and the public access way will eventually narrow.[484] In the case of a shoreline migration conservation easement, the landowners will often be most concerned about restrictions on shore protection and requirements to remove the buildings as the shore retreats. Owners may be willing to agree to provisions allowing the public access way to migrate inland, if they are satisfied with the restrictions on shore protection and maintaining their homes.

For government regulations, by contrast, migrating public access (beyond what would happen automatically from the public trust doctrine) can raise property rights issues. In Texas, there was some confusion from 1986 until 2010 about whether the boundary of the public's legal right to access along the beach migrates inland with the dune vegetation line, or if the boundary remains fixed where it was when public access was established. The state's policy was that the access migrates inland, and the state assumed that it was simply implementing a longstanding public access right that had been explicitly codified.[485] But in 2010, the Texas Supreme Court held that although the mean high water line (which defines land ownership) is a rolling boundary, the public access boundary does not roll.[486] In effect, the court held that the state's policy to ensure that dry beach access is a rolling easement had reset the rolling design boundary inland from mean high water to the dune vegetation line, without a statutory basis for doing so.[487] After the court ruling, the state suspended planned beach nourishment projects until beachfront landowners agreed to transfer rolling easements on their properties,[488] which would have been unnecessary under the previous interpretation of Texas law.

Roads and other shorefront land uses. As with public access, a rolling easement meant to ensure that roads, utilities, parks, or waterfront businesses are able to migrate inland must explicitly say that the boundary migrates inland, and specify the shoreline with which they migrate. If a 50-foot roadway about 70 feet inland of the beach is the objective, for example, then the rolling easement could provide for a road easement to all dry land within 120 feet inland of the vegetation line. In this case, nonconforming structures may also have to be removed if they encroach more than (for example) 10 feet because they will become road hazards and otherwise defeat the purpose of the rolling roadway easement.

6.1.2 The Area of Habitat or Public Access Initially

Shrinks before Migrating Inland.

Some landowners negotiating shoreline migration easements may agree to forgo shore protection, but not agree to the automatic inland migration of all existing legal and natural boundaries. State or local governments may conclude that the inland migration of some boundaries is essential to putting a community on a retreat pathway, but that requiring other boundaries to migrate inland would unreasonably interfere with private property rights. In either case, the rolling easement that results will provide for an initial narrowing of the public resources along the shore, after which the remaining rolling boundaries will migrate inland with the retreating shore.

Public Access. Along beaches to which the public has access for reasons other than the public trust doctrine, the boundary of public access is generally a fixed line. Existing rolling easement regulations in such areas generally do not ensure that the boundary of public access migrates inland. As a result, the portion of the beach to which the public has access might narrow until the public trust boundary[489] reaches the fixed line of public access. From that day on, public access will migrate inland; but it would only include the public trust lands. The public's ability to use the beach would be impaired?especially if homes remain seaward of the dune vegetation line (see Photos 33 to 35).

|

|

|

Photos 33 to 35. Most states show

flexibility on removal of buildings on the

beach as a result of erosion. Top: Westerly,

Rhode Island (March 2003). Middle: Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina (June 2002). Bottom:

Folly Beach, South Carolina (April 2004).

Photo source: ©James G. Titus, used by

permission. |

As a practical matter, public access up to the dune vegetation line has often been established based on the longstanding use of the beach, under various legal doctrines.[490] If the public continues to use the beach up to the dune vegetation line, then public access along the shore could migrate inland, not as a matter of law, but through the repeated re-establishment of new public easements.[491] Landowners are entitled to prevent trespassing. Whether they do so depends on the energy of the wave environment, because posting signs or fences is impractical, hazardous, and often prohibited along shores with substantial waves (compare Photos 36 and 37 with Photos 33 to 35). Nevertheless, homes standing on the beach tend to discourage pedestrian access.

A conscious recognition that the public access line does not roll inland with the dune vegetation line would not necessarily mean that access along the shore must eventually be reduced to only those areas below mean high water. Some landowners may agree to allow the public to walk along the shore some distance seaward of the dune line, which could be set sufficiently inland of mean high water to provide a reasonable pedestrian way, but sufficiently seaward of the vegetation line to not interfere with the owners' use of their property. In many states, courts have not explicitly decided whether the public has access to the part of the beach between the average high water mark (or wet/dry line) and mean high water; so it is possible that in some states where private ownership extends down to mean high water (or even mean low water) the common law would allow access below the average high water mark.[492] Thus a regulation that sets the public access line as the average high water mark might not interfere with existing property rights, and a shoreline migration easement that sets public access accordingly may be viewed as a clarification rather than setting the access line seaward of where the law requires.[493]

Wetlands. The state as property owner can prohibit construction and other activities on public trust wetlands, typically low marsh. Regulations restrict the conversion of privately owned tidal wetlands to dry land.[494] A state may be able to persuade a court to order removal of shore protection that blocks the inland migration of public trust tidal wetlands under the common law of nuisance.[495] If so, a regulation that requires the same thing does not impair property rights. But that argument does not apply to shore protection that prevents privately owned dry land from becoming privately owned high marsh. Although no court has decided the question, a state or local government might decide that it lacks the authority to ensure the migration of high marsh, and accordingly set the rolling design boundary at mean high water. As a result, the high marsh would be lost while the low marsh continued to migrate inland. Similarly, a landowner negotiating a shoreline migration easement might agree to forgo shore protection but not to remove the home until it is submerged at low tide. Such an arrangement would enable the public access line and wetlands to migrate inland, but the building line would—in effect—be reset to mean low water, before rolling inland.

The accommodation pathway [496] can also narrow habitat or public access initially, before migrating inland. (Accommodation is a general response to sea level rise in which people continue to occupy an area but shore protection is precluded.[497]) For purposes of shore protection, the rolling design boundary along an estuary may be the upper edge of wetlands. But the boundary defining removal of homes may be well seaward of the upper edge of tidal wetlands (e.g. mean low water)—or might not roll at all.

|

|

| Photos 36 and 37. Where the wave climate is reasonably light, landowners are better able to discourage trespassing on the dry beach. Left: fences along the dry beach of Long Island Sound (Knollwood Beach, Connecticut; March 2003). Right: a sign along the shore of Orient Harbor near the eastern end of Long Island. (Orient, New York; September 2006). [Photo source: ©James G. Titus, used by permission]. |

6.1.3 Inland Redefinitions of Public Access and Other

Boundaries

As a general rule, a rolling easement policy need not be the occasion to reset the shoreline boundary defining where the public has access. The purpose of the rolling easement is to ensure that the inland boundary of shoreline habitat or public access migrates inland along with the retreating shore, not to push that limit father inland relative to the shore. Nevertheless, a rolling easement policy can also be adopted as part of a government policy or private transaction that clarifies or modifies the public access boundary for other reasons. In many states, for example, the public has greater access along the ocean than along other bodies of water;[498] eventually a uniform set of rules may be adopted in a given state. Shore protection policies and projects often re-define the private/public boundary from mean high water to the dune vegetation line, to ensure that publicly funded beach nourishment is only provided to beaches that are open to the public.[499] Rolling easements can also be part of such transactions.[500]

Along estuarine shores, even though the public (usually) owns up to mean high water, a policy designed to allow wetlands to migrate inland may require structures to be removed once they encroach seaward of the tidal wetlands, which generally extend to spring high water (or farther).[501]

The question of what the design boundary should be for environmental and safety reasons is different from the question regarding payment to landowners. A rolling easement policy under which the existing public-trust boundary migrates inland might not require compensation under the U.S. Constitution or the common law (especially in an undeveloped area) because this boundary has migrated inland for centuries, and landowners do not have an expectation of maintaining a home that stands in state-owned waters. A policy that provides for the inland migration of public access obtained by other means is more likely to alter property rights and require compensation. The Texas Supreme Court, for example, limited the situations in which the dry beach easement rolls inland, relying on the Legislature's intent to not alter property rights; but it also explicitly stated that the holding did not apply to the public/private boundary established by the public trust doctrine.[502]

Resetting the public/private boundary inland of where it is today would be even more likely to require compensation. Along estuarine shores, a rolling easement that requires removal of a home on privately owned wetlands above mean high water would interfere more with the reasonable expectations of a landowner than would a requirement to remove a structure standing in shallow water or the publicly owned wetlands below mean high water.

6.1.5 Alternatives to a Rolling Design Boundar.

A rolling easement policy can also be based on time or migration of the shoreline. For example, instead of prohibiting shore protection without qualification—which existing rolling easement policies typically do—an easement or regulation could allow shore protection for a specific period (e.g., 75 years) to provide some assurance of property value.[503] Such a qualification may be particularly appropriate if shore protection is unlikely to be needed before then anyway, because the environmental result is likely to be the same as if there were no qualification. But ensuring that the rolling easement will not take the property for two generations can help make a potential home buyer more willing to buy land subject to the easement, and hence make a developer more willing to place rolling easements on an entire development.

Structures can also be prohibited based on time alone. For example, the existing shoreline could be surveyed and a seaward limit line could be specified to move inland by five feet per year. Such a predetermined rate would only roughly correspond with the natural shore migration, but it would provide property owners with certainty regarding their land tenure. This approach may be useful for lands likely to be vulnerable within a few decades, during which time a community may be willing to temporarily provide beach nourishment or artificial wetland accretion if shorelines migrate faster than assumed.[504] Existing setback policies already use a linear extrapolation of historic erosion rates to prevent construction on land likely to be eroded.

Finally, a rolling easement policy can be based on sea level. Restrictions could be based on the elevations of land relative to the rising sea. Alternatively, land could revert to another owner when the sea rises to a particular level.[505] In this case, if entire parcels revert at once, one would have to pick a single elevation to represent vulnerability to sea level rise. Alternatives include the average elevation of the parcel and the elevation of the home site. If a survey shows the home site to be 4 feet above the upper edge of low marsh vegetation in an area where the boundary between low and high marsh is recognized as mean high water, then a 4-foot rise in sea level would submerge the home site in the absence of shore protection. In such a case, the deed might specify that the land reverts when sea level rises 4 feet above the current level.[506]

One could pick a nearby station where NOAA regularly measures sea level, and specify (for example) that when average annual sea level rises 4 feet above sea level for the current tidal epoch as measured by NOAA at that station (or the nearest station if NOAA later changes procedures), the land will revert. Alternatively, a deed might transfer title based on measured sea level relative to a benchmark elevation. If the home site is 7 feet above the North Atlantic Vertical Datum, then the deed might specify that when mean high water at that location reaches an elevation of 7 feet above the North Atlantic Vertical Datum, the land reverts.[507] In the former case, creation of the rolling easement requires agreement regarding the current land elevation relative to sea level, to establish a baseline; but over time it would be relatively easy for all of the parties to keep track of (or prove to a court) how much sea level had risen at the NOAA tide station.[508] In the latter case, the deed could be drafted based on an elevation survey (or lidar elevation data), but it may be necessary to install a tide gauge and collect data for a suitably long period of time to determine sea level at that location.

[474] See, e.g., Maryland Law Review, supra note 7, at 1316 Fig 3 (showing all boundaries migrating inland).

[475] See supra § 3.1.2.1.

[476] See, e.g., Tex. Nat. Res. Code Ann. § 61.0185 (providing for two-year delay in proceedings to remove from the beach a house that was previously landward of the vegetation, as long as it is not seaward of mean high tide); CCSP, supra note 3, at 173 (pictures of homes standing on the public beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina over a 1-year period); and infra Photo 35 (picture of homes standing on the dry beach at Folly Beach, South Carolina). See also Hirtz v. State of Tex., 773 F. Supp. 6 (S.D. Texas 1991) (“The owners may lose their houses and their land entirely, and they have to allow public access over what used to be exclusively theirs, but they do not have to neglect the maintenance of what is actually there now.”) That opinion was later vacated on purely procedural grounds. Hirtz v. State of Tex., 974 F. 2d 663 (5th Cir. 1992).

[477] See supra note 293 and accompanying text.

[478] Rhode Island's rules prohibit shore protection along dunes, Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Program Rules § 210.7(D)(2); coastal barriers, id. § 210.2(D)(4); wetlands in Class 1 waters, id. § 210.3(C)(3); and beaches along Class 1 and 2 waters, id. § 210.1(C)(2). Construction along dune areas must be set back 30–60 times the annual erosion rate plus 25 feet inland of the crest of the primary dune, id. §§ 210.7 (C)(2) and 210.7(A)(2), but there is no similar setback for wetlands.

[479] See, e.g., supra note 152 and accompanying text (discussing towns in Massachusetts that restrict grade elevation and shore protection within 50 feet inland of tidal wetlands)

[480] See supra notes 43–54 and accompanying text.

[481] See, e.g., State v. Ibbison, 448 A.2d 728, 732 (RI, 1982). See also supra notes 46–47 and accompanying text.

[482] See supra note 51 (Louisiana), 52 (Hawaii and perhaps Washington), 58 (New Jersey and perhaps Oregon) and accompanying text.

[483] See supra § 2.2.2.

[484] See supra notes 83–88 and accompanying text.

[485] See supra § 3.1.2

[486] Id. The confusion resulted largely because the Open Beaches Act did not explicitly provide for the inland migration of the public easement along the dry beach as shores eroded, but instead directed the state to defend the public easement consistent with existing property rights. State officials and intermediate courts assumed that the common law easement along the dry beach migrated inland, but in 2010 the Texas Supreme Court held that it did not (under most circumstances). And because the statute explicitly adopted the common law easement boundaries rather than explicitly providing for inland migration, and expressly said that it has no impact on land titles, the holding that the public dry beach easement did not roll under the common law implied that the statute had not created a rolling easement either. Had the statute explicitly redefined how the boundary migrated—at the risk of changing pre-existing property rights which were somewhat unclear—then by 2010, it would have been clear for 50 years that coastal property was subject to a rolling dry beach easement.

[487] Id.

[488] See, e.g., supra note 411 and accompanying text.

[489] In many states, the inland extent of public trust access is unclear along beaches where the average high water mark is well inland of the mean high water line. What is clear, however, is that public trust access does not extend all the way to the vegetation line. See supra § 2.2.1.

[490] See supra note 62–64 and accompanying text.

[491] See e.g. Severance v Patterson, No. 09-0387 (Tex. 2010) (“New public easements on the adjoining private properties may be established if proven pursuant to the Open Beaches Act or the common law”).

[492] The traditional public trust doctrine gave the public access up to the ordinary high water mark, and courts have generally held that the public has access to the entire wet beach. Court opinions defining “ordinary high water mark” as mean high water have focused on the difference between spring high water and mean high water, and not addressed the tendency for mean high water to be tens of feet seaward of the average high water mark. The cases have defined mean high water as the line that separates the wet beach from the dry beach, seemingly unaware that the wet/dry line is well inland of mean high water. See generally, supra § 2.2.1.

[493] See supra notes 43–49 and 60, and accompanying text (citing court opinions that define the inland boundary of public ownership as mean high water but have left open the possibility that public access may extend farther inland).

[494] See e.g. 33 U.S.C. § 1344.

[495] See, e.g., Maryland Law Review, supra note 7, at 1371–1374 (arguing that a tideland owner could seek removal of a bulkhead as a nuisance) and supra notes 266–400 (discussing case where tribe owning tidelands sought removal of shore protection structure under nuisance law).

[496] See supra § 1.1.

[497] See supra § 1.1 for a brief discussion of the accommodation and other pathways

[498] See e.g. Tex. Nat. Res. Code § 61.01 (defining “public beach” as beaches along the Gulf of Mexico) and McDonald v. Halvorson, 780 P.2d 714, 724 (Or. 1989) (holding that the doctrine of custom which provides the public access along dry sand beaches on the Pacific Ocean does not apply to other beaches).

[499] The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers requires that the public have access along and to any beaches that are nourished as part of a federal project. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Digest of Water Resources Policies and Authorities 14-1: Shore Protection, EP-1165-2-1 (Washington, DC 1996). See also CCSP, supra note 3, at 121–122. Florida fixes the boundary at the mean high water line, and then claims all land created seaward of that line under the doctrine of avulsion. See, e.g., Walton County v. Stop the Beach Renourishment, Inc., 998 So.2d 1102, 1107–1109, 1115–1118 (Florida 2008).

[500] See, e.g., supra note 411 and accompanying text (citing a new policy in Texas which requires waterfront owners to convey a rolling easement on their lands before the state will place sand onto their privately owned beaches).

[501] See, e.g.,, J.G. Titus & J. Wang, Maps of Lands Close to

Sea Level along the Middle Atlantic Coast of the United States: An Elevation

Data Set to Use While Waiting for LIDAR, in J.G. Titus & E.M.

Strange (editors), Background Documents Supporting Climate Change Science

Program Synthesis and Assessment Product 4.1, EPA-430-R-07-004

9

& 27 (2008) (winds rather than tides determine the extent of

tidal wetlands in nanotidal estuaries, and even in microtidal areas lands that

are flooded irregularly by the winds can have tidal wetlands).

[502] Severance v. Patterson, No. 09-0387 (Tex. 2010).

[503] Depending on how it is structured, such a safety valve may have tax consequences. See supra notes

244 and 473.

[504] To avoid various uncertainties, a property owner and a land trust or local government may prefer to negotiate a specific abandonment date once submergence becomes imminent enough to predict with reasonable accuracy. See infra note 595.

[505] See supra § 3.2.2.

[506] In this situation, the entire parcel would transfer to the

rolling easement holder at the same time as when the public trust doctrine would transfer

ownership of the house site to the public (in

most states). Regulations prohibiting grade elevation could enable wetlands to migrate

inland before the reversion. In such a case, the easement holder would

only own the portion of the parcel above the house site. Alternatively, a possibility

of reverter could

transfer ownership when spring high water submerges the home site; such a case would in effect, reset the

rolling design boundary inland (or design plane upward).

[507] For a discussion of reference elevations and their relationship to wetlands and sea level rise, see Titus & Wang, supra note 501, at 6-24. That report includes a diagram similar to the figure in supra Box 2, but with the reference elevations also displayed. Id. at 7.

[508] See e.g. Chris Zervas, Sea Level Variations of the United States: 1854–2006. (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2009). The NOAA website regularly updates sea level for stations around the United States.

This page contains a section from: James G. Titus, Rolling Easements, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA-430-R-11-001 (2011). The report was originally published by EPA's Climate Ready Estuary Program in June 2011. The full report (PDF, 176 pp., 7 MB) is also available from the EPA web site.

For additional reports focused on the implications of rising sea level, go to Sea Level Rise Reports.

Roadmap for Chapters 6 to 9

Roadmap for Chapters 6 to 9