- Causes of Future Sea Level Rise

- Elevation Maps

- Will we really lose all that land?

- Sea Level Rise Planning Maps

3.2.2 Defeasible Estates and Future Interests in Land

A completely different way to ensure that ecosystems and public access migrate inland is for land ownership to terminate when something happens. Homeowners usually own land in fee simple absolute, which means that ownership lasts forever. An alternative approach is to split the land title into two periods of time: If a parcel is 4 feet above spring high water, for example, the buyer could own the land until the sea rises 4 feet, after which ownership would be transferred to TLC. Under such an arrangement, the buyer owns a defeasible estate while TLC owns a future interest. Other parcels with different elevations could transfer when the sea reaches different heights.[233] (See Figure 9.)

The eventuality of the land transferring to TLC would tend to ensure that ecosystems and access along the shore migrate inland, for at least two reasons. First, at about the time when a homeowner would otherwise have to engage in shore protection to prevent wetlands or the beach from migrating onto her land, the future interest will transfer ownership to an organization whose mission includes ensuring natural shoreline migration. Second, the prospect of the land reverting to TLC limits any incentive to build shore protection, because the owner will lose the land anyway.[234]

The common law of property defined several ways of dividing land ownership into a defeasible estate and a future interest in land. This section examines three:

- Buyer owns a fee simple determinable for an unknown period of time (e.g., until sea level rises 4 feet), after which title reverts back to the developer, who retains the possibility of reverter.

- Buyer owns a fee simple subject to a condition subsequent unless she does something (e.g., erects shore protection) that triggers a power of termination, at which point the developer can go to court to demand possession of the land.

- Original owner retains a fee simple subject to a condition subsequent by transferring to TLC an executory interest entitling it to take over the property when something happens (e.g., sea level rises 4 feet).

Possibility of Reverter. Consider a deed that says that the developer is granting the land to the buyer “for as long as it takes sea level to rise 4 feet above the level that prevailed in the 1980–2001 tidal epoch.” The buyer owns a “fee simple determinable,” which is a type of “defeasible estate”, that is, an interest in land that may end at some point in the future.[235] The developer retains a “possibility of reverter” because the property will revert to the developer if and when sea level rises 4 feet. The developer can sell or donate the possibility of reverter to TLC or a government agency, in which case the property will revert to that entity whenever the sea rises 4 feet. (If some or all of the land is seaward of the public/private boundary by that time, ownership will have already been transferred to the state; and thus will not be transferred to TLC).

Retaining a possibility of reverter has been common in the case of land provided for railroads.[236] Owners of farms and other large parcels were often more willing (i.e., willing at a lower price) to allow a railroad through their lands than to sell the land, which could leave the eventual use unknown and beyond their control. The railroads preferred to purchase a fee simple determinable at a lower price because they had no need for the land beyond operation of the railroad. Similarly, landowners who wanted to see a church or school nearby often conveyed land “for as long as” the church or school operated.[237] Conveying land “for so long as” the sea does not rise enough to submerge it is analogous to that classic land use arrangement. A would-be land seller concerned about the implications of rising sea level may be more willing to sell if the home will be removed as the sea threatens it, than if the home will be protected at the expense of the environment.[238] The buyer may prefer a fee simple determinable at a lower price because she is not interested in paying extra for the right to maintain a home below sea level.

Providing for land titles to transfer upon a specific event has several advantages over a shoreline migration conservation easement:

- TLC, as the holder of the future interest, does not have to monitor possible efforts by landowners to extend their tenure by surreptitiously adding fill or otherwise thwarting inland migration of the ecosystem, because the property reverts regardless. (The owners can try to extend their tenure by assisting efforts to slow sea level rise, but doing so would not interfere with the environmental purpose of a rolling easement.[239])

- TLC does not have a duty to manage the property, which can be costly for a conservation easement. (See Chapter 8.) There is no risk that failure to manage the easement before sea level rises 4 feet will be deemed an abandonment of the easement. TLC simply takes over the land when the time comes (if the land has not already reverted to the state). But TLC does have the option of intervening if the landowner does something that unreasonably threatens its interest in the land.[240]

- Under the common law, anyone may own a possibility of reverter. A community organization or even the owner of the next home back may hold the interest—unlike a conservation easement, which must be owned by a government agency or a qualified conservation organization. (Some states have enacted statutes limiting ownership to charities or government agencies.)

- Although future sea level rise is uncertain, over the short run it is often more predictable than shoreline erosion.[241] Therefore, in the final decade or so before the property reverts to TLC, the landowner can plan and invest with a reasonable understanding of the property's remaining longevity.[242]

- Financial mechanisms are likely to eventually make it possible to hedge against the risk of sea level rise, adding further predictability to the risks faced by a homeowner whose title transfers upon a given sea level.[243]

- If buyer resistance unreasonably depresses the value of land subject to a rolling easement, a possibility of reverter can be drafted to ensure (for example) that the reversion does not occur before 75 years hence, without fundamentally changing its character. Such a time limit may be more difficult to accomplish with a conservation easement.[244]

The most important drawback to the possibility of reverter is that statutes in some states now limit its duration to a few decades,[245] which is too short for ensuring that wetlands migrate inland as sea level rises.

A reversion can be based on shoreline erosion instead of sea level rise. Along sandy beaches, elevation alone usually understates how soon the land will be converted to tidelands and open water. Thus, a possibility of reverter based on sea level rise may transfer the land to TLC decades after the owner erects shore protection. Conversely, if the shore erodes more slowly than expected, the home may still be well inland and usable when the future interest awards the land to TLC.

Power of Termination. Another approach is for the land to change hands based on what the landowner does, instead of environmental factors. Whatever activity can be precluded by a shoreline migration conservation easement can also be the activity that triggers a reversion. For example, the property can revert if the owner undertakes shore protection without permission of TLC, and fails to remove it upon TLC's request. The deed can be drafted to say “…but if the grantee or her heirs construct a bulkhead, revetment, or any hard shore protection structure, or deliberately elevate the average elevation grade of the parcel, then the grantor and her heirs shall have the power of termination.” The buyer will own a “fee simple subject to a condition” while the seller retains the “power of termination”(sometimes called a “right of re-entry”).[246] The owner will have a strong incentive to avoid shore protection: With a shoreline migration easement, if the owner erects a shore protection structure, TLC can go to court to seek removal of the structure and monetary damages to cover the costs for challenging the violation. But with a power of termination, TLC can ask the court to award the property to TLC. Removal of the shore protection structure and management of the property would then become the responsibility of TLC.

The Difference between Possibility of Reverter and Power of Termination. The key difference between our two example deeds is that the first deed conveys land for an unknown duration (until the sea rises 4 feet), while the second deed transfers the land back to the seller if the buyer does something (in this case, attempt shore protection). Courts have generally been suspicious of punitive arrangements that cause land to be forfeited.[247] But they have also distinguished forfeitures from the natural termination of an ownership interest when its purpose has been fulfilled. [248] Conveying an estate for the needed duration (e.g., the life of a railroad), has been viewed more favorably by courts than arrangements under which land might be forfeited for doing something (e.g., selling liquor)—especially where the harm done was far less than the value of the land being forfeited.[249] The common law treated the power of termination as a forfeiture, while the possibility of reverter was simply a natural expiration.[250] During the 20th century, the concern about punitive forfeitures led both courts and legislatures in some states to restrict the ability of property owners to create and enforce both of these approaches (although governments and charities are sometimes exempt).[251] In some cases the two approaches have been merged into a single legal interest.[252] Thus to avoid the possible appearance of a forfeiture, rolling easements based on future interests in land should be drafted to distinguish the reversion to nature intended by the rolling easement, from the potentially punitive or arbitrary forfeiture that has traditionally concerned the courts.

Land trusts regularly use conservation easements,[253] but not future interests in land.[254] Under most circumstances, a conservation easement with a power of termination clause would seem punitive. Owners who donate or sell typical conservation easements (or buy property with an easement already in place) intend to keep their land and do not generally wish to take the chance of losing the property due to a possible disagreement over cutting trees or enlarging a house. But rolling easements are different: the entire point is to ensure that the land is given over to the migrating wetlands and beaches. A transfer of title from a rolling easement would not be an unreasonable forfeiture for violating a condition but rather a fulfillment of the original intent of the grant.[255]

Efforts at shore protection signal that the time to allow the land to revert to nature has arrived. An owner willing to promise to not prevent the sea from taking over her land would logically agree that if her heirs did try to prevent the sea from taking over the land, then the land would be awarded to an entity that will ensure that the sea takes over the land. Courts sometimes avoid a forfeiture by ordering the owner to do what the condition requires (e.g., stop selling liquor).[256] But in this case, removing the shore protection causes the same result as forfeiting the property. The land becomes submerged, reverts to nature, and becomes part of the public trust whether it is first transferred to TLC or a court simply issues an injunction against the shore protection.

Executory Interest. Rolling easements based on a possibility of reverter or power of termination are future interests in land that the original owner (e.g., the developer) retains when granting the (less than absolute) fee simple interest to new owners (e.g., home buyers). Those future interests can then be sold or donated to a land trust or government agency. In some cases, the opposite transaction may be desired. Suppose the developer cancels the development and sells the entire parcel to a new owner; and the new owner later wants to transfer a rolling easement in which she retains the land until the sea rises 4 feet, after which title goes to TLC. The net effect is the same as if the developer had retained a possibility of reverter and donated it to TLC.[257] But in this case, the future interest does not revert to a previous owner, so it is called an “executory interest.”[258]

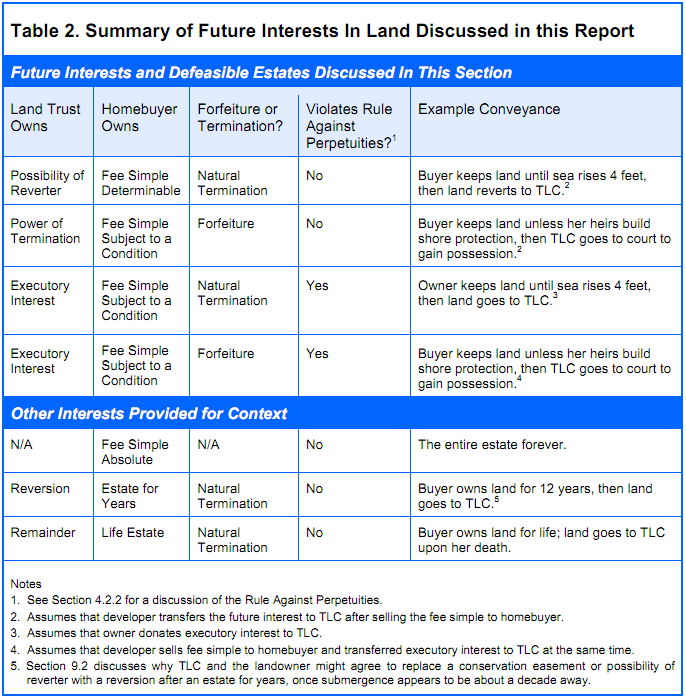

Summary. Table 2 summarizes the

defeasible estates and future interests in land discussed in this section. As a

general rule, courts have been more inclined to enforce a possibility of

reverter than either a power of termination or an executory interest.[259] It is often

possible to create a possibility of reverter that accomplishes the goals of a

power of termination or executory interest.[260] Thus, for the

rest of this primer, wherever we discuss future interests, we focus on a

possibility of reverter rather than the other two approaches.

[233]

Id. at 83–85.

[234] Planning will be even easier if title changes on a date certain. It is possible that in the final decade or so, the parties will agree to revise the deed so that title changes on a date certain, based on a forecast of sea level rise. See infra note 595 and accompanying text.

[236] See, e.g., National

Wildlife Federation v. ICC, 850 F.2d 694, 705 (D.C. Cir.

1988).

[237] See, e.g., O. L.

Browder, Defeasible Fee Estates in

Oklahoma—An Addendum, 6 Okla. L.

Rev. 482, 482–84 (1953).

[238] The seller could be motivated by personal concern about the

environment, environmental permit requirements, or the adverse impact of shore

protection on adjacent parcels that she also

owns.

[239] In some estuaries, tidal gates may be erected to slow the rate

at which mean high water rises. Although a single landowner is not likely to substantially slow the rate

of global sea level rise, coastal landowners collectively could become a

powerful force for reducing greenhouse

gases.

[240] Under the

doctrine of waste, TLC has the option of monitoring the

property to ensure that the owner does not do anything to harm its

possibility of reverter. The doctrine of waste is an equitable doctrine of

property law designed to prevent someone in temporary possession of a piece of

property, such as a life tenant, from using the property in a way that unfairly

harms the value of the estate that will eventually be transferred to a future

interest holder. See Restatement

of Property: Future Interests 189, 193 (1936) (detailing the action that

the owner of a future interest can take when the owner of the present estate

engages in threatening conduct). The Restatement implies that if

the contingent interest is likely to vest, the current estate holder's duty to

the reversionary interest holder is (essentially) to manage the property as if

she were the owner of the entire estate. See, e.g., Restatement of Property: Future

Interests 140, 193. The future interest holder has no duty to take action

under the doctrine of waste; she simply risks losing whatever she might have

saved by taking action.

[241]

Storm erosion is less predictable than gradual submergence by rising sea

level. Although the average annual

mean tide level can also fluctuate, the 19.6-year running average that would be

used to calculate sea level in a given year fluctuates

less.

[242] The predictability of the property's longevity would be even

greater if title were to change on a date certain. Converting a defeasible estate into an

estate that transfers (for example) 10 years hence could be a final step in the

management of such a rolling easement. See note 595

and accompanying text.

[243]

Daniel Alexandre Bloch, James Annan, & Justin Bowles, Applying Climate

Derivatives to Flood Risk Management (June 20, 2010). Available at SSRN:

http://ssrn.com/abstract=1627644.

[244] The Uniform

Conservation Easement Act allows easements to specify time limits. Federal tax

laws, however, disallow deductions unless the easements are

perpetual, which

might include

taking effect immediately, see infra

note 473.

Land trusts generally do not accept conservation easements that do not take

effect until a remote date in the future. In this case, there is a possibility (albeit unlikely) that a home

will be threatened before 75 years.

A remote contingency that would destroy the conservation value does not

disqualify the easement. 26 CFR § 1.170A-14 (g)(3); but it is unclear whether an

unlikely contingency that would postpone—but not destroy—the conservation value

would be viewed more or less harshly. A conservation easement that prohibits shore protection but

allows a home to remain for 75 years

is less likely to lose its tax

deductibility than a conservation easement that allows shore protection for 75

years

[245]

See infra note 392 and accompanying text .

[247] Joseph

Story, 2 Commentaries on Equity Jurisprudence

as Administered in England and America 544–547

§§

1314–1316

(1839) (“Where a penalty or forfeiture is

designed merely

as a security to

enforce [an] obligation,” equity will ensure that

the obligation is

met, but will not assist with a forfeiture that causes one party to suffer a

loss that is disproportionate to the loss of the other party).

Livingston v.

Tompkins, 4 Johns, Ch. 415, 8 Am. Dec. 604 (1820); Jones v. Guaranty & Indemnity Co., 101 U.S. 622, 628 (1880)

(“A court of equity abhors forfeitures, and will not lend its aid to

enforce them.”); Nielsen v. Woods, 687

P.2d 486, 489 (Colorado Court of Appeals, 1984). (“[E]]quity will not enforce a forfeiture [of land

due to possibility of reverter] if the party insisting upon it may be

made whole otherwise.”) Cf. Restatement (Second) of Contracts: Liquidated

Damages and Penalties § 355 (1981) (a contract clause with

liquidated damages greater than the actual damages that were reasonably expected

to result from a breach is unenforceable because it is a penalty). U.C.C. 2-718

(2001) (limiting liquidated damages to a reasonable expectation of actual

damages).

[248] See Hornbook on Property, supra note 203,

at 156 §§

15–16. A fee simple

determinable with a possibility of reverter is generally conveyed for a specific

purpose whose duration is unknown, such as for the purposes of a school or

railroad, e.g., McDougall v. Palo Alto

etc. School Dist., 212 Cal. App. 2d

422 (1963). Equity would have no reason to intervene to stop the reversion,

because reversion is not punishment for closing the school or the railroad, but

simply the natural termination of the estate which had been conveyed for a

specific reason. By contrast,

equity may intervene to stop a forfeiture resulting from the failure to comply

with a condition, to ensure that neither party is subject to hardship. Davis v.

Gray, 83 U.S. 203, 230–31 (1873). See

also supra note 247.

[249]

The

preference for conveyances of duration for a purpose over forfeitures has

generally been accomplished by looking directly at the forfeiture issue

regardless of how the interest is defined. Because (for example) the conveyance

of land for a school can either be expressed as providing the land for the

needed duration or as threatening a forfeiture as punishment for closing the

school, some scholars have suggested that today there is little difference other

than some of the rights flowing from each interest. See, e.g. Frona Powell, Defeasible Fees and the Nature

of Real Property, 40 Kansas Law

Review 411, 415–410 (1992) (suggesting that the chief distinction is the

mechanism for how the estate terminates and not discussing the difference in

purpose for the two estates). Allison Dunham, Possibility of Reverter and Powers of

Termination—Fraternal or Identical Twins? 20 U. Chi. L. Rev. 215, 225–229 (1953)

(discussing the difference between the natural termination of an estate and a

forfeiture, and how courts struggle when the intent of the parties diverges from

the deed language as drafted).

The “power of termination/right

of re-entry”cannot be sold in some jurisdictions. Hornbook on Property, supra note 203,

at 164, and can be viewed as waived if the owner fails to take legal action. Id. at 165. Contingent remainders and

executory interests are vulnerable to the common law Rule Against Perpetuities.

Id. at 168. See infra §

4.2.2.

[252] Cal. Civ. Code §

885.020 (“Every interest that would be at common law a possibility of

reverter is deemed to be and is enforceable as a power of

termination”).

[253] E.g.,

Julia D. Mahoney, Perpetual Restrictions

on Land and the Problem of the Future, 88 Va. L. Rev. 740, 741 (2002) (citing

Land Trust Alliance, 1998 National Land

Trust Census and Julie Ann

Gustanski, Protecting the Land:

Conservation Easements, Voluntary Actions, and Private Lands, in

Julie Ann Gustanski and Roderick H.

Squires, eds., Protecting the

Land: Conservation Easements Past, Present and Future (Washington DC,

Island Press,

2000)).

[254]

One exception is that conservation easements sometimes include a clause that

transfers the easement from one land to another if the first land trust fails to

fulfill its responsibilities. See

infra note 280 and accompanying text.

[255] One who

designs a rolling easement based on future interests must be prepared for

possible skepticism of the arrangement, even though the traditional reasons for

the skepticism do not apply to a rolling easement. Traditionally, reversions

were usually based on how the landholder used the property, such as a

railroad. See, e.g., Preseault v. ICC, 494

[256]

See supra note 247. See also Powell, supra note 249,

at 425–26 (discussing cases where courts avoided a forfeiture by construing

language that appeared to intend a power of termination or possibility of

reverter as only being a covenant).

[257]

See Hornbook on Property, supra note 203,

at 176–79 (discussing how the same result can occur either by directly

transferring an executory interest to X or by retaining a possibility of

reverter and later conveying it to X).

[258] See Hornbook on Property, supra note 203,

at 169–173. If the owner wants a tax deduction, a shoreline

migration easement may be preferable because the IRS does not generally allow

deductions for donations of a future interest in land, unless that is all the

donor owns in the particular parcel.

[259] In general,

executory interests are subject to the common law Rule Against Perpetuities,

which provides that the interest must be guaranteed to vest (if ever) within 21

years of the death of a party named in the deed, Hornbook on Property, supra note 203,

at 213–215. That period could often be too short for a rolling easement,

especially if sea level rises more slowly than expected. Several states have

repealed or reformed this rule. Although charities are sometimes exempt, the

reform efforts have not considered environmental or historic preservation as

specific purposes. See infra §

4.2.2.

[260] E.g., instead of donating a rolling

easement as an executory interest, the owner could transfer a fee simple

determinable to her son, and retain a possibility of

reverter. She could then donate that possibility of reverter to The Land

Conservancy and her

son could later transfer the fee simple determinable back to her. Although this

superficially seems to be an easy way to always defeat the Rule Against

Perpetuities, that rule was meant to prevent complicated arrangements

that

keep land within a

family indefinitely by allocating ownership interests based on various

contingencies. See, e.g., Angela M. Vallario, Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Rule against

Perpetuities, 25 J.

Legis. 141, 142–145

(1999). The rule was never intended to prevent environmental conservation

or other transfers resulting from the natural termination of a particular use.

If the

son retains the

fee simple determinable,

the

This page contains a section from: James G. Titus, Rolling Easements, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA‑430‑R‑11‑001 (2011). The report was originally published by EPA's Climate Ready Estuary Program in June 2011. The full report (PDF, 176 pp., 7 MB) is also available from the EPA web site.

For additional reports focused on the implications of rising sea level, go to Sea Level Rise Reports.

3.2.1 Easements and Covenants

3.2.1 Easements and Covenants