Shore Protection and Retreat: Environmental Consequences

Related Links

U.S. Global Change Research Program

Other EPA-sponsored Climate Change Science Program Synthesis and Assessment Reports

From

Shore Protection and Retreat by James G. Titus and Michael Craghan (2009), which was chapter 6 of the Bush Administration's

published sea level rise assessment, entitled Coastal Sensitivity to Sea Level Rise

Outline of the Chapter

- 6.1 Techniques for Shore Protection and Retreat

- 6.1.1 Shore Protection

- 6.1.2 Retreat

- 6.1.3 Combinations of Shore Protection and Retreat

- 6.2: What factors influence the decision whether to protect or retreat?

- 6.3: What are the environmental consequences of retreat and shore protection?

- 6.4: What are the societal consequences of retreat and shore protection?

- 6.5: How sustainable are retreat and shore protection?

6.3 What are the environmental consequences of retreat and shore protection?

In the natural setting, sea-level rise can significantly alter barrier islands and estuarine environments (see Chapters 3, 4, and 5). Because a policy of retreat allows natural processes to work, the environmental impacts of retreat in a developed area can be similar to the impacts of sea-level rise in the natural setting, provided that management practices are adopted to restore lands to approximately their natural condition before they are inundated, eroded, or flooded. In the absence of management practices, possible environmental implications of retreat include:

- Contamination of estuarine waters from flooding of hazardous waste sites (Flynn et al., 1984) or areas where homes and businesses store toxic chemicals;

- Increased flooding (Wilcoxen, 1986; Titus et al., 1987) or infiltration into public sewer systems (Zimmerman and Cusker, 2001);

- Groundwater contamination as septic tanks and their drain fields become submerged;

- Debris from abandoned structures; and

- Interference with the ability of wetlands to keep pace or migrate inland due to features of the built landscape (e.g., elevated roadbeds, drainage ditches, and impermeable surfaces).

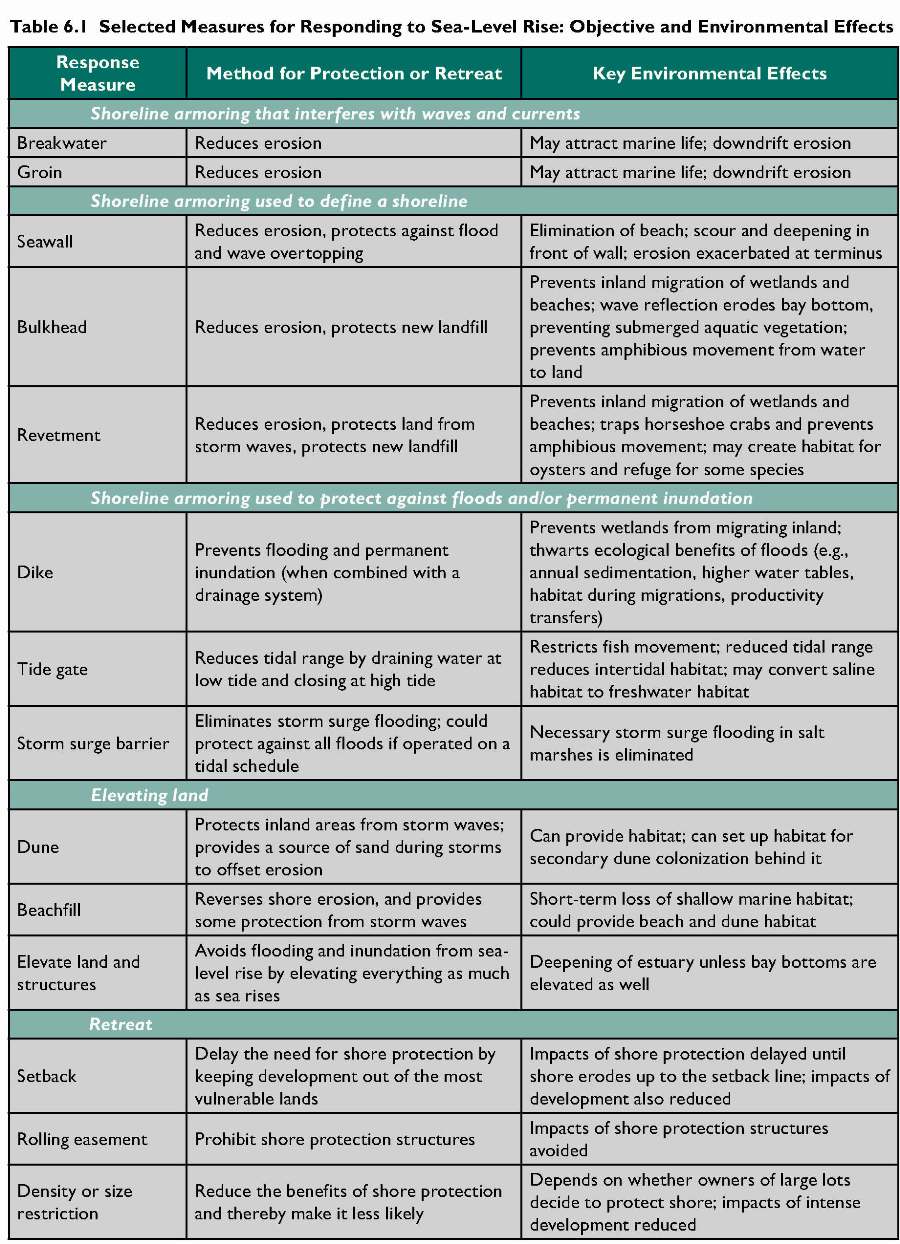

Shore protection generally has a greater environmental impact than retreat (see Table 6.1). The impacts of beach nourishment and other soft approaches are different than the impacts of shoreline armoring.

Beach nourishment affects the environment of both the beach being filled and the nearby seafloor “borrow areas” that are dredged to provide the sand. Adding large quantities of sand to a beach is potentially disruptive to turtles and birds that nest on dunes and to the burrowing species that inhabit the beach (NRC, 1995), though less disruptive in the long term than replacing the beach and dunes with a hard structure. The impact on the borrow areas is a greater concern: the highest quality sand for nourishment is often contained in a variety of shoals which are essential habitat for shellfish and related organisms (USACE, 2002). For this reason, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has denied permits to dredge sand for beach nourishment in New England (e.g., NOAA Fisheries Service, 2008; USACE, 2008a). As technology improves to recover smaller, thinner deposits of sand offshore, a greater area of ocean floor must be disrupted to provide a given volume of sand. Moreover, as sea level rises, the required volume is likely to increase, further expanding the disruption to the ocean floor.

As sea level rises, shoreline armoring eventually eliminates ocean beaches (IPCC, 1990); estuarine beaches (Titus, 1998), wetlands (IPCC, 1990), mudflats (Galbraith et al., 2002), and very shallow open water areas by blocking their landward migration. By redirecting wave energy, these structures can increase estuarine water depths and turbidity nearby, and thereby decrease intertidal habitat and submerged aquatic vegetation. The more environmentally sensitive “living shoreline” approaches to shore protection preserve a narrow strip of habitat along the shore (NRC, 2007); however, they do not allow large-scale wetland migration. To the extent that these approaches create or preserve beach and marsh habitat, it is at the expense of the shallow water habitat that would otherwise develop at the same location.

The issue of wetland and beach migration has received considerable attention in the scientific, planning, and legal literature for the last few decades (Barth and Titus, 1984; NRC, 1987; IPCC, 1990). Wetlands and beaches provide important natural resources, wildlife habitat, and storm protection (see Chapter 5). As sea level rises, wetlands and beaches can potentially migrate inland as new areas become subjected to waves and tidal inundation—but not if human activities prevent such a migration. For example, early estimates (e.g., U.S. EPA, 1989) suggested that a 70 cm rise in sea level over the course of a century would convert 65 percent of the existing mid-Atlantic wetlands to open water, and that this region would experience a 65 percent overall loss if all shores were protected so that no new wetlands could form inland. That loss would only be 27 percent, however, if new wetlands were able to form on undeveloped lands, and 16 percent if existing developed areas converted to marsh as well. The results in Chapter 4 are broadly consistent with the 1989 study.

Very little land has been set aside for the express purpose of ensuring that wetlands and other tidal habitat can migrate inland as sea level rises (see Chapter 11 of this Product; Titus, 2000), but those who own and manage estuarine conservation lands do allow wetlands to migrate onto adjacent dry land. With a few notable exceptions7, the managers of most conservation lands along the ocean and large bays allow beaches to erode as well (see Chapter 11). The potential for landward migration of coastal wetlands is limited by the likelihood that many shorelines will be preserved for existing land uses (e.g., U.S. EPA, 1989; IPCC, 1990; Nicholls et al., 1999). Some preliminary studies (e.g., Titus, 2004) indicate that in the mid-Atlantic region, the land potentially available for new wetland formation would be almost twice as great if future shore protection is limited to lands that are already developed, than if both developed and legally developable lands are protected.

- For previous reports focused on the implications of rising sea level, go to More Sea Level Rise Reports.

6.2: What factors influence the decision whether to protect or retreat?

6.2: What factors influence the decision whether to protect or retreat?